Home

VII. SITE SITUATED KNOWLEDGE

23/03/2019

“ Ecofeminists have perhaps been most insistent on some version of the world as active subject, not as resource to be mapped and appropriated in bourgeois, Marxist, or masculinist projects. Acknowledging the agency of the world in knowledge makes room for some unsettling possibilities, including a sense of the world’s independent sense of humour.”

“”Our” problem (,) is how to have simultaneously an account of radical historical contingency for all knowledge claims and knowing subjects, a critical practice for recognising our own “semiotic technologies” for making meanings, and a no-nonsense commitment to faithful accounts of a real world, one that can be partially shared and that is friendly to earth wide projects of finite freedom, adequate material abundance, modest meaning in suffering, and limited happiness.”

Throughout this year I became aware of the fragile aspect of science as truth. I was fortunate enough to cross path with several writings of Donna Harraway on the mater. In her opinion science is rhetoric. It is a specific language which aim is to “persuade social actors that one’s manufactured knowledge is a route to a desired form of very objective power (imperialism).” By describing science as a mean to maintain and perpetuate masculine ideas of progress, quest and global-understanding, I realised that scepticism toward science is unnecessary mere paranoia. For the present, science remains one way of understanding and rationalising reality (sadly influenced by imperialist and capitalist motives), yet, there might be other ways to construct narratives about the world in which we try to operate. Significantly, I share her opinion according to which this language should be unpacked, revealed and held responsible for the discursive games and consequences it subtends. Especially in considering its entanglement with hegemonic structures or rational thinking and sense making. Considering the significant crisis we are currently facing, one must acknowledge the “structure of facts and artefacts, as well as of language-mediated actors in the knowledge game.” To work our way through alternative models of thinking we ought to de-resonate through sentient practices as well as making and caring for one another.

As mentioned hitherto, in her text, D. Harraway formulates a sort of plaidoyer for new forms of scientific knowledge through feminist praxis. While criticising scientific “objectivity” (if such thing actually exist), she introduces new methodologies built upon site-situatedness, common-ing, non-binary-ness, eco-techno-feminism and humour. Opposing feminist objectivism and situated knowledge to science quest for a fantasised objective truth, she formulates a radical critique “against” the rhetorical nature of scientific “objective-ness” and its hostility (as militarised heritage). In doing so she inquires commonly used terms like Relativism & totalisation as “god” rhetorical tricks turning non-situated vision into scientific mythology.

Farther than observation, she offers rhetorical and practical tools for “us”, the sentients, to problematise and formulate alternative facts and figures through the creation of deconstructing tools as ways to reveal the entanglements at play in scientific discourses. Hither, I got reminded of Guattari and Deleuze theorising of philosophy as an opportunity to invent new concepts and shape novel forms of knowledge which de-construct pre-existing ones. She also formulates a necessity for feminist praxis to transcend dualist pointers like good/bad, mind/body, culture/nature… meanwhile applying a constructionist argumentation. It is equally significant to notice her refusal to neither learn the “modern-man” tools nor apply self-help feminist theories.

“ To learn how to see faithfully from another’s point of view, even when the other is our own machine”

Another aspect with a rich echo to my current research is that of reclaiming vision. In her words, vision is honed to perfection in the history of science and tied to militarism, capitalism, colonialism and male supremacy. “Vision is always a question of the power to see” Contrary to the Aristotelian tradition of sensorium hierarchy paired to cartesian dualism, Haraway proposes an embodied standpoint to counter the conquering gaze of the scientific realm. She states that “Struggles over what will count as rational accounts of the world are struggles over how to see?” In doing so, she formulates an accountability for the responsibility of visualisation’s instruments as compounded in disembodiment. Looking at the machine we created to gaze at “us” from a non-pervasive standpoint; my current practice similarly seeks to formulate alternative observatory apparatuses which could enable a more diverse and less colonising clinical gaze.

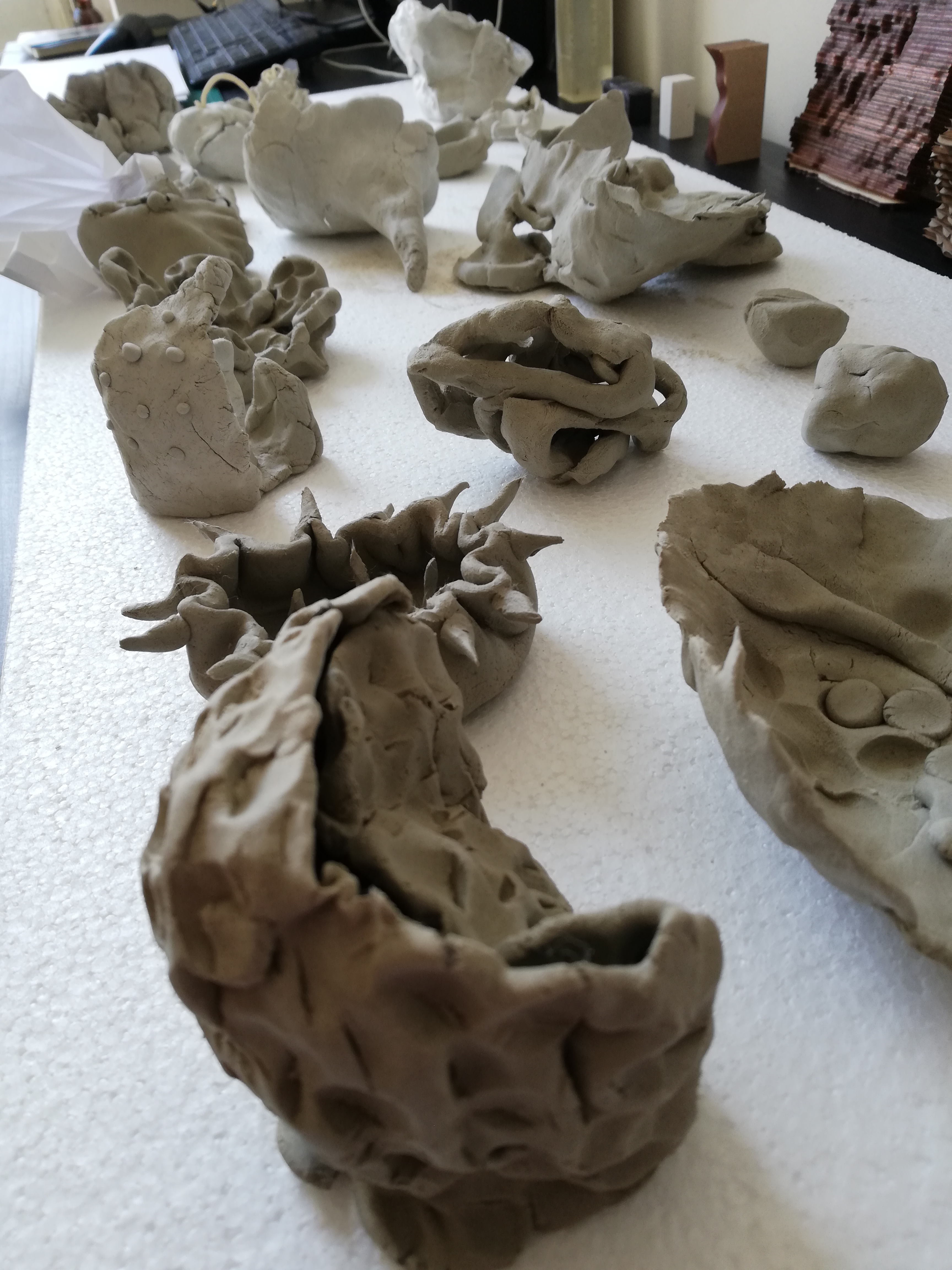

Still looking at the observatory realm, she informs us about the semantical signification of “objects of knowledge” — the objects being looked at. Indeed, such probe is suspicious in its passivity and inhert-ness, meanwhile becoming a resource for instrumentalism and disguise for dominating discourses. In doing so she addresses the risk of “reduction” of the object to the ephemera of discursive production and social construction. This aspect of her thinking is something that I implement in my research project Uterii where I formulate a necessity to create new image processing protocols and machine in the configuration of the clinical image of female Uterus. In thinking the reconfiguration of the machine and its protocol I apply this idea of object-of knowledge agency, therefrom trying to shape them as un-fixed protocols which could embrace the alter, even alien, aspect of our bodies.

“Feminist embodiment, then, is not about fixed location in reified body, female or other wise, but about nodes in field, inflections in orientations and responsibility for difference in material-semiotic fields of meaning.”

Ultimately, another feature I recall in my research is that of passionate detachment in relation to practices of commoning. Indeed, throughout the text she inquires how we could see from bellow by means of conversation and solidarity toward the creation of “critical knowledges sustaining the possibility of webs of connections called solidarity in politics and shared conversations in epistemology”. She clearly formulates a critic of french-feminism and marxism she argues for eco-feminism as a praxis emphasising key concepts like contestation, care and passionate construction. Terms which coincide with my ongoing interest for post-structuralist French theorists and a general acceptation for my inability to structure my design process. By far, it is fair to believe that eco-feminism in Haraway’s definition is quintessential to the formulation of alternative methods toward a criticism of neoliberal capitalism. Indeed, her call for this new feminist praxis seems legitimate whistle one witnesses the failure of the sad-socialists agenda for whom “it is impossible”. In this regard, humour, optimism, but also productive distances(-iation) and solidarity by means of caring seem to be more adequate tools to counter the consequences of years of masculinist scientific agendas and politics.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), p.575.

IMAGES

Dorothea Tanning - Some Roses and Their Phantoms (1952)

Uterii_001: Project collective research moment (03/2019)