Home

V. SUCHMAN & AI FIGURATION

05/11/18

"My project is clearly indebted to these efforts, which provide the reconceptualizations needed to move outside the frame of categorical purification and opposition between the social and technical, person and artifact."

What do those claims and encounters tell us about the particular cultural imaginaries that inform these technoscience initiatives, and how they might be otherwise?"

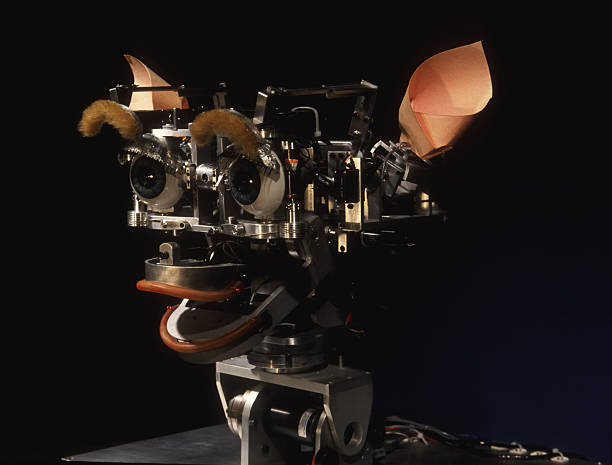

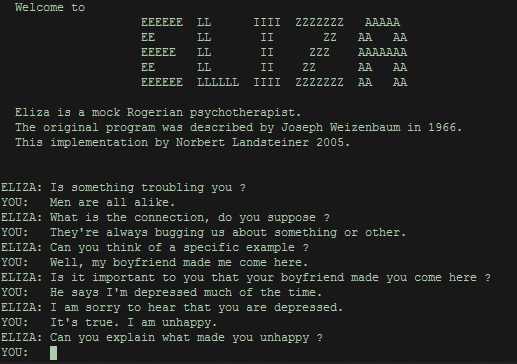

Emerging from the need to question the preconceived “cognitivist rationality” of humanlike machines and the imaginaries generating and generated by techno sciences, Lucy Shuman’s book “Human–Machine Reconfigurations, Plans and Situated Actions, 2nd Edition” is of importance for whom desires to critically assess human-machine engineering, figuration and interaction. In the three chapters; figuring the Human in AI and Robotics; Demystifications and Re-enchantments of the Humanlike Machine and Reconfigurations, Lucy Shuman challenges several cross-disciplinary aspects of Human-machine interaction. Therefrom she formulates new possibilities for our understanding and portrayal of human machine inter-related id-entities, their bodies and matter. Using observations from anthropological, sociological, scientific and what seems to be an ethnological methodology, the text is relevant in that it demystifies the “Machine singularity/uncanny” scapegoat. Thence offering a theoretical ground for artistic critical reconfiguration of AI, robotics and human imaginaries. From Donna Harraway’s notion of “Figuration” to Brooks' “Situated Robotics”, the text is rich in references and dense in concepts -- which is sometime overwhelming especially if one is not aware of the multiple theories she refers to.

Some aspects of the two-first chapters are of substantial relevance while envisaging my own practice. For instance, the possibilities for the female recon-figuration through the re-definition of “agency” within human and machine interaction. Through analysing concepts of embodiment, emotion and sensibility, Shuman’s inquires the legitimacy of the mind and body dissociation inscribed in engineering practices by invoking feminist theory for AI and robotics as new ways to think an "us and them". Thereupon, she advances concepts of “Affective computing” and a phenomenological approach to techno-scientific practices.

“Affective computing would transform machines from slaves chained to the limits of logic into thoughtful, observant collaborators. Such devices may never replicate human emotional experience. But if their developers are correct, even modest emotional talents would change machines from datacrunching savants into perceptive actors in human society. At stake are multibillion-dollar markets for electronic tutors, robots, advisers and even psychotherapy assistants” (Piller 2001: A8)

Later on she warns us about the “manipulated, isolated, replicated, standardized, quantified “ effect of affective rationality meanwhile affective encounters could be considered as singular moments, qualitative rather than quantifiable commodities — A Bergsonian “élan vital” rather than a causal effect. Further, she addresses the relationships induced in human-machine interaction — from the creator to the machine, the machine and its environment, the machine as a labor symbol… Meanwhile, she depicts AI and Robotics as a global entity, which socio-materiality results from an entanglement of operating networks, people and objects with their own agencies.

“At the same time, the enchanted object’s effects are crucially tied to the indecipherability of prior social action in the resulting artifact.”

Chapters II and III challenges machine’s materiality and how it can reconfigure notions of corporeality toward a new conception of bodies. Drifting on concepts such as prosthetic qualities of AI, Robots and human inter-action, she illustrates very vividly an aspect of human machine collaboration in medicinal technology often overlooked. That of the proprioceptive shift perceived by doctors using prosthetic technologies. Here, human machine interaction allows a new sensory perception of the “other Body” leading to a unique symbiosis experience with the patient.

“When the patient’s body is distributed by technology, the surgeon’s body reunites it through the circuit of his or her own body” (ibid.: 8).

Meanwhile she develops and argument according to which human and artefacts are mutually constituted yet asymmetrical. Her last chapter is a good basis to understand the artists/designer responsibility in shaping technological artefacts with a considerate awareness of the societal portrayal at play, both threatening and hopeful. In such context, designers are responsible for a techno-materiality that is social, political and critical at once.

“How then might we locate conditions for action and possibilities for intervention in the specificities of more mundane socio material assemblages? “ — “Rather than a process that stops at the point of hand-off from production to consumption, design is as an ongoing process of (re-)production over time and across sites. Just what, then, is the role of the professional designer? Although in no way obviating the specific knowledges and material practices of the designer, the object of design must shift. “ — “Rather than holding stable and separate the identities of “the designer” and “user,” the latter work as categories describing persons differently positioned, at different moments, and/or with different histories and future investments in projects of technology development “ — “Responsibility on this view is met neither through control nor abdication but in ongoing practical, critical, and generative acts of engagement. The point in the end is not to assign agency either to persons or to things but to identify the materialization of subjects, objects, and the relations between them as an effect, more and less durable and contestable, of ongoing sociomaterial practices."

Reading those chapters and Amy Ireland’s article "Black Circuit: Code for the Numbers to Come" // e-flux #80 made me conscious and critical AI representation within mainstream media.

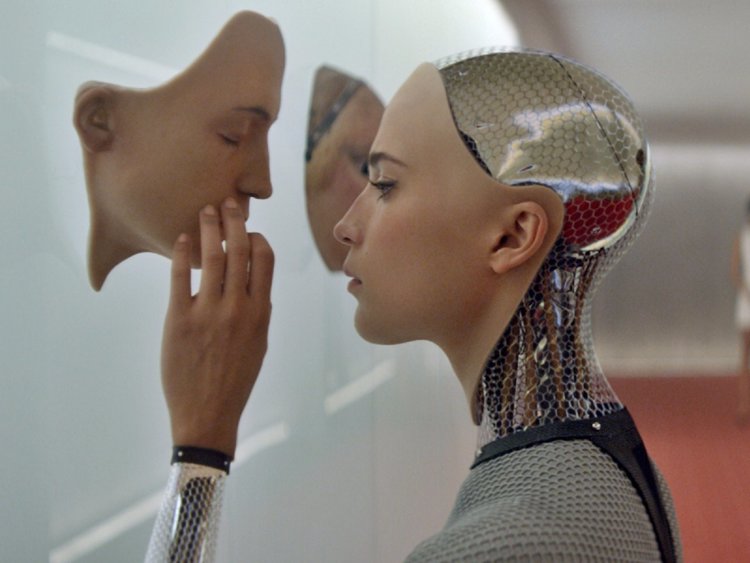

"Because she hath made her self the servant of each, therefore is she become the mistress of all."

Constructing her article around the myth of BABALON and mainstream AI female embodiment in recent films, Amy Ireland illustrates how AI are often depicts as women due to their ability to fake, seduce, and trap within a logic of replication rather then reproduction. She illustrates her argumentation on two movies: Alex Garland's Ex Machina (2015 ) and Gabe Ibáñez's 2014 movies Automata in which AI are females. Invoking Sadie Plant’s critic of the female as a negative missing part and its contingent emancipation through the technological 0 constitutive of the 1, the author proposes that we see uncanniness of AI female bodies as an emancipatory reclaiming of female identity over that of the man.

“When one goes deeper than the imputed absence of a sex, woman-reproducing-man becomes woman-reproducing-woman in an anorganic becoming that – as the cyberpositive formulation of the replicative economy belonging to the black circuit – recodes time as it inverts the user-tool relationship to reveal history as loop with a twist."

"At the peak of his triumph, the culmination of his machinic erections, man confronts the system he built for his own protection and finds it is female and dangerous."

Yet, the limitation to two examples felt incomplete, pushing me to research how this embodiment could also be addressed through other scopes. To illustrate my research, I looked into AI’s Instagram influencers. Contemporary versions of Hatsume Miku, I came across lilmiquela and her supremacist trump supporter homologue Bermuda. Here AI is embodied as female in both corporeality and social construct. Those AI bodies are turned into marketing commodities, incarnation of our imaginaries failure and a certain compliance to patriarchy 3.0. Contrary to Ava in Ex-machine, Shudu, Bermuda or lilmiquela have no agency. They are the perfect slick agglomeration of stereotypical commodified forms — a constant flux of sign/image. Finally, in both Instagram’s AI and mainstream movies, females AI are always sexually objectified, perfectly rendered into slick bodies hiding the very perverse beauty of our sexes.

If we are to portray AI as female, it is then our duty (as artefact makers) to shape a female body that transcends the patriarchal capitalist projection of eroticism and perfidy through female machine uncanniness.

Our bodies are slimy, malleable, soft, sticky, filled with moist, why wouldn’t the machine be likewise?

If the female cyborg is slick, I rather not be.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Suchman, Lucy. Human-machine reconfigurations: Plans and situated actions. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Ireland, A. (2019). Black Circuit: Code for the Numbers to Come - Journal #80 March 2017 - e-flux. [online] E-flux.com. Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/80/100016/black-circuit-code-for-the-numbers-to-come/ [Accessed 27 Mar. 2019].